“When the going gets tough, the tough take a nap.” — Tom Hodgkinson, British Writer

1

New Disease?

Humour me and imagine! You have just been blessed with a child. The doctor announces to you pleasantly, “Congratulations, it’s a healthy baby boy. We’ve completed all the preliminary tests and everything looks good.”

She smiles reassuringly and starts walking toward the door. However, before exiting the room she turns around and says,

“There is just one thing. From this moment onwards, and for the rest of your child’s entire life, he will repeatedly and routinely lapse into a state of apparent coma. It might even resemble death at times. And while his body lies still his mind will often be filled with stunning, bizarre hallucinations. This state will consume one-third of his life and I have absolutely no idea why he’ll do it, or what it is for. Good luck!”

Most of us feel that this scenario painted by Walker2 sums up the medical knowledge about sleep. But, does it?

Sleep is vital!

Sleep is important to us – as important if not more, as food and exercise.3

We might turn mad if we are not allowed to lapse into this ‘coma’ as Methrew Walker has put it.! Hallucinations start if we are sleep deprived for 72 hours.4 Repeated exposure to sleep deprivation leads to cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, endocrine disturbances and susceptibility to infections and cancer.

What is sleep?

We all know that an organism is sleeping when it-

- adopts a stereotypical position- often horizontal.

- has lowered muscle tone especially in postural (antigravity) skeletal muscles. A sleeping organism will be draped over whatever supports it underneath.

- shows no response to routine environmental stimuli.

- This state is reversible, differentiating it from coma, anaesthesia, hibernation, and death. And lastly,

- Sleep adheres to a reliable timed pattern across the day, regulated by a natural circadian rhythm. Humans have evolved to be diurnal, so we have a preference for being awake throughout the day and sleeping at night.

During sleep, one’s ears are still “hearing.”Similarly, the signals from all the sense organs are still being sent to one’s brain, but these signals are hit by a barricade set up in the thalamus (the sensory gateway to cortex). So, while sleeping, the brain has lost contact with the outside world.

Does the brain sleep?

The sense of time is lost during sleep. One has to look at a watch to see how much one has slept. Interestingly, the brain’s internal clock continues to catalog time with incredible precision. If one sets an alarm for 6:00 a.m. he or she may miraculously wake up at 5:58 a.m., unassisted, right before the alarm.

Brain definitely does not sleep. It is highly active during our sleep and is busy doing a lot of housekeeping tasks. Externally, scientists record various stages of sleep. There are cycles of dreaming (also called REM or rapid eye movement) sleep interspersed with deep (also called NREM or non-REM) sleep, which has further 4 stages.

To each his own

Most of us evolve an individual sleeping pattern. There are “morning larks” and “night owls.” Some people are active and bright early in the morning. Others like to sleep till late in the mornings, with their best time being late evening. In an institutional life such as the Army, ‘night owls’ complain that they are more sleep-deprived, having to wake up with the larks for PT, but not being able to fall asleep until far later in the evening after the lights-out.

Pacemaker?

The suprachiasmatic nucleus is the pacemaker. Two hormones are involved – melatonin and adenosine. The dark surroundings (of night) lead to release of melatonin from the pineal gland, which announces that it is time to sleep. 5

Adenosine levels build up in the brain with each waking minute and creates pressure and desire to sleep. Once one sleeps, the adenosine is removed by degradation.

Caffeine (as in coffee) can mute the adenosine signals by occupying its receptors.Caffeine levels peak after consumption in about 30 minutes and have a half life of 5-7 hours, may be longer in older people. Slow and rapid metabolizers are genetically determined by the enzymes in the liver. 6

Sleep stages

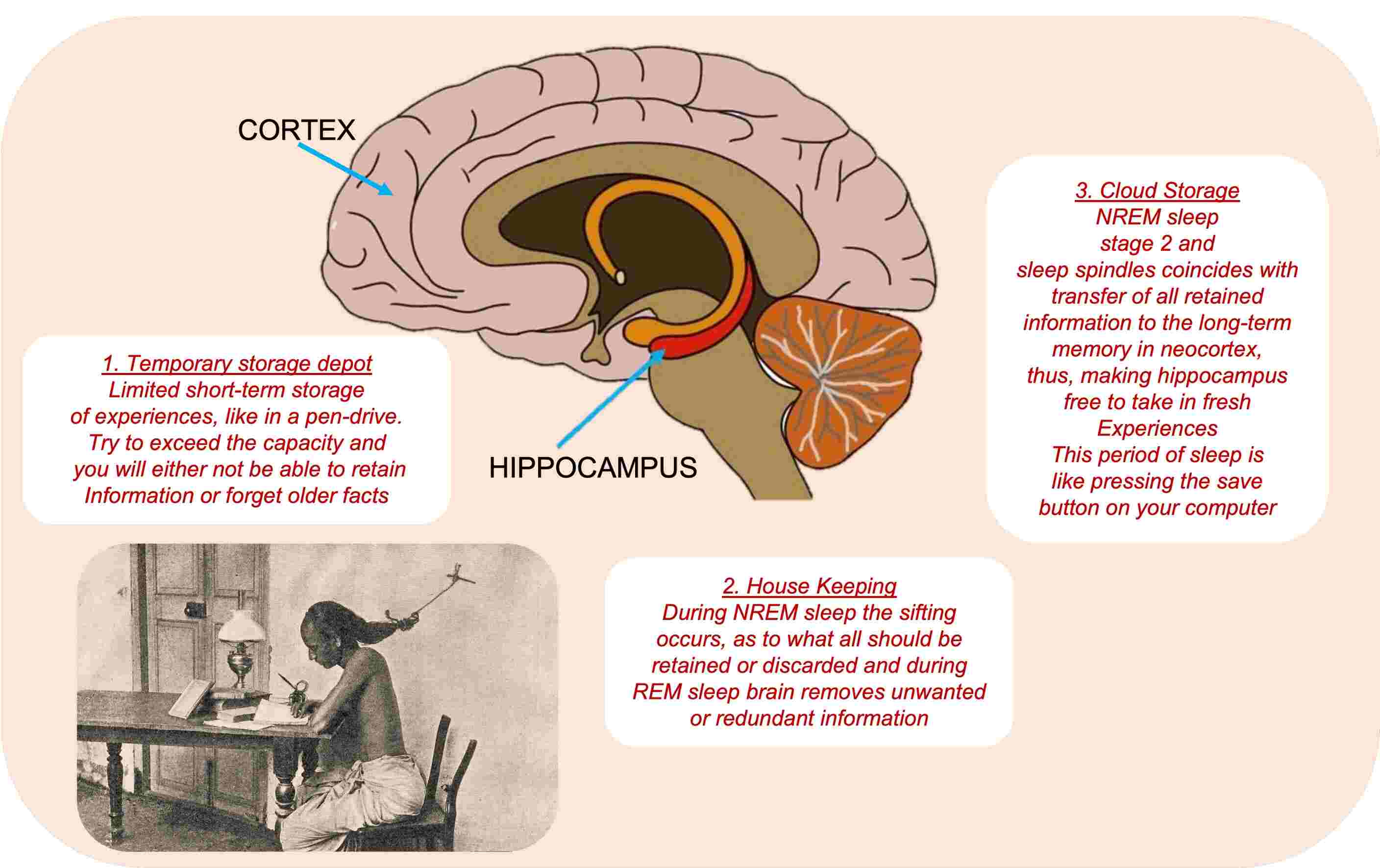

As noted above, during 7-8 hours of sleep, we pass through several cyclic phases or stages. A key function of deep sleep, which predominates early in the night, is to do the work of weeding out (selecting experiences to be removed) unnecessary neural connections. In contrast, the dreaming stage (rapid eye movement or REM sleep), which prevails later in the night, plays a role in strengthening the residual connections. (See Figure-1)7

Sleep and memory

A finger-shaped structure deep inside of our brain, the hippocampus serves as a short-term reservoir, or temporary information store, for new memories.8 Unfortunately, the hippocampus has a limited storage capacity, like a USB memory stick. Exceed its capacity and you run the risk of not being able to add more information or, equally bad, overwriting one memory with another: a mishap called interference forgetting.(Figure-1)

Smaller bites followed by a good night’s sleep is the key to good retention especially in the student-life. Cramming everything just before exams with sleep deprivation is the most inefficient method.

Age and Sleep

Before birth babies spend most of their time in REM like state interspersed with remodeling NREM. Disturbance in sleep at this stage is related to autism spectrum disorders.9, 10

During mid- and late childhood, as the last neural growth spurt is being completed, there is a sharp rise in deep-sleep intensity. Failure of this spurt has been linked to synaptic pruning and later development of schizophrenia.11 At nine-year-age, the circadian rhythm would have the child asleep earlier, by around nine p.m., driven in part by the rising tide of melatonin at this time in children.

During puberty, the timing of the suprachiasmatic nucleus is shifted progressively later. By the time that same individual has reached sixteen years of age, his/her circadian rhythm has undergone a dramatic shift in its rhythm with teenagers sleeping late and getting up late. As teenagers mature, the adult pattern kicks in.

Elderly adults need as much sleep, but are simply less able to generate that sleep.12 They wake up frequently, have less of the youthful deep sleep and there is sleep fragmentation. The release of melatonin is early, causing drowsiness, and early snooze clears away the adenosine buildup. Poor memory and poor sleep in old age are significantly interrelated.

Poor deep sleep is one of the most underappreciated factors contributing to cognitive and medical ill health in the elderly, including issues of diabetes, depression, chronic pain, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Sleep and sports

Sleep also improves the motor skills of junior, amateur, and elite athletes across the sports as diverse as tennis, basketball, football, soccer, and rowing. So much so that, in 2015, the International Olympic Committee published a consensus statement highlighting the critical importance of, and essential need for, sleep in athletic development across all sports for men and women. 13

The most sophisticated, potent, and powerful—not to mention legal—performance enhancer that has real game-winning potential is sleep. These claims can be backed up by over 750 scientific studies that have investigated the relationship between sleep and human performance, many of which have studied professional and elite athletes. 14

Sleep loss and health

Sleep loss inflicts devastating effects on the brain. Strong associations have been described with numerous neurological and psychiatric conditions (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, suicide, stroke, and chronic pain),15, 16 17 and on every physiological system of the body, further contributing to countless disorders and disease (e.g., cancer, diabetes, heart attacks, infertility, weight gain, obesity, and immune deficiency). No facet of the human body is spared the crippling, noxious harm of sleep loss.

There are many ways in which a lack of adequate sleep kills. One brain function that buckles under even the smallest dose of sleep deprivation is concentration. Every hour, someone dies in a traffic accident due to lack of sleep. The common cause of accidents is a momentary lapse in concentration, called a microsleep.18 Obese truck drivers are especially at risk as they have chronic, severe sleep deprivation due to associated obstructive sleep apnea.

The power of power naps

Power naps lasting 15-20 minutes are resorted to by overworked executives who erroneously believe that it is all one needs to survive and function with perfect, or even acceptable, acumen. There is no scientific evidence that it can replace normal sleep.

Sleep deprivation has been associated with depression and extreme negative mood which can infuse an individual with a sense of worthlessness, together with ideas of questioning life’s value. Insufficient sleep has also been linked to aggression, bullying, and behavioral problems in children across a range of ages. A similar relationship between a lack of sleep and violence has been observed

Heart attacks

A 2011 study tracked 474,684 men and women of varied ages, races, and ethnicities across eight different countries. Short sleep was associated with more than a 45 percent greater risk of fatal and non-fatal coronary events within seven to twenty-five years from the start of the study.

Obesity

When the sleep becomes short, one steadily gains weight. Leptin (Satiety hormone) and Ghrelin (Hunger hormone) are both altered in wrong directions by sleep deprivation. Experiments 19, 20, 30, 21 have shown that a strong rise of hunger pangs and increased appetite occurred rapidly, by just the second day of short sleeping. cravings for sweets (e.g., cookies, chocolate, and ice cream), heavy-hitting carbohydrate-rich foods (e.g., bread and pasta), and salty snacks (e.g., potato chips) all increased by 30 to 40 percent when sleep was reduced by several hours each night.

Reproductive health

Experiments on a group of lean, healthy young males in their mid-twenties showed a marked drop in testosterone levels if one limited them to five hours of sleep for one week. The size of the hormonal blunting effect was so large that it effectively “aged” a man by ten to fifteen years in terms of testosterone virility. Mathew Walker says, poor-quality sleep leads to nearly a 30 percent lower sperm count and is associated with smaller sized testicles.

Even in women, there is a 20 percent drop in follicular-releasing hormone and often suffer from issues of sub-fertility that reduced the ability to get pregnant. When they do become pregnant, they are more likely to suffer a miscarriage in the first trimester.

Infections and immunity

An intimate and bidirectional association exists between your sleep and the immune system. Sleep fights against infection and sickness by deploying all manner of weaponry within your immune arsenal, cladding you with protection. When you do fall ill, the immune system actively stimulates the sleep system, demanding more bed rest to help reinforce the war effort. Reduce sleep even for a single night, and that invisible suit of immune resilience is rudely stripped from your body.22

Sleep and Cancer

It doesn’t require many nights of short sleeping before the body is rendered immunologically weak, and here the risk of cancer becomes important. Natural killer (NK) cells are an elite and powerful squadron within the ranks of your immune system whose job it is to identify dangerous foreign elements and eliminate them. One such foreign entity that NK cells will target are malignant (cancerous) tumour cells. This function is deficient when one sleeps less than recommended 7-8 hours a day.

It has been shown23 that a single night of four hours of sleep—such as going to bed at three a.m. and waking up at seven a.m.—swept away 70 percent of the natural killer cells circulating in the immune system, relative to a full eight-hour night of sleep.

Gozal24 has shown that immune cells, called tumor-associated-macrophages are a root cause of the cancerous influence of sleep disruption. He found that sleep deprivation will diminish M1 macrophages, that otherwise help combat cancer. Sleep disruption conversely boosted levels of an alternative form of macrophages, called M2 cells, which permit cancer growth. The scientific evidence linking disrupted sleep-wake rhythms and cancer is now so damning that the World Health Organization has officially classified nighttime shift work as a “carcinogen.”

Can sleeping pills or alcohol help?

Sleeping pills or alcohol do not provide natural sleep, can damage health, and increase the risk of life-threatening diseases.25, 26

Sleeping pills, and alcohol are sedatives and effectively knock out the higher regions of your brain’s cortex. It also results in a number of unwanted side effects, including next-day grogginess, daytime forgetfulness, performing actions at night of which you are not conscious and slowed reaction times during the day. The waking grogginess can lead people to reach for coffee or tea to rev themselves up with caffeine. That caffeine, in turn, makes it harder for the individual to fall asleep at next night, worsening the insomnia.

Medication-induced sleep does not provide the same restorative immune benefits as natural sleep. Sleeping pill taking individuals were 30 to 40 percent more likely to develop cancer within the two-and-a-half-year period in a study than those who were having normal sleep. While the search for more sophisticated sleep drugs continues, currently, the most effective of these is called cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or CBT-I. It builds on basic sleep hygiene principles that are described below.

Help, what do I do if I can not sleep!

Twelve key tips are recommended by National Institutes of Health website and are summarised below.27

1. Stick to a sleep schedule. Go to bed (and wake up) at the same time each day.

2. Exercise is great, but not too late in the day. Try to exercise at least thirty minutes on most days but avoid it during two to three hours before your bedtime.

3. Avoid caffeine and nicotine. Especially in the late afternoon.

4. Avoid alcoholic drinks before bed. Having a nightcap or alcoholic beverage before sleep may help one relax, but heavy use robs one of REM sleep, keeping one in the lighter stages of sleep. Heavy alcohol ingestion also may contribute to impairment in breathing at night. One also tends to wake up in the middle of the night when the effect of the alcohol has worn off.

5. Avoid large meals and beverages late at night. A light snack is okay. Drinking too many fluids at night can cause frequent awakenings to urinate.

6. If possible, avoid medicines that delay or disrupt your sleep. Some commonly prescribed heart, blood pressure, or asthma medications, as well as some over-the-counter and herbal remedies for coughs, colds, or allergies, can disrupt sleep patterns.

7. Don’t take naps after 3 p.m. Naps can help make up for lost sleep, but late afternoon naps can make it harder to fall asleep at night.

8. Relax before bed. Don’t take work to bed. Don’t overschedule your day so that no time is left for unwinding. A relaxing activity, such as reading or listening to music, should be part of your bedtime ritual.

9. Take a hot bath before bed. The bath can help you relax and lower your body temperature, making one more ready to sleep.

10. Bedroom should be darkened, cooled, quiet and should be gadget-free.

11. Have the right sunlight exposure. Daylight is key to regulating daily sleep patterns. Try to get outside in natural sunlight for at least thirty minutes each day. You should get at least an hour of exposure to morning sunlight and turn down the lights before bedtime.

12. Don’t lie in bed awake. If you find yourself still awake after staying in bed for more than twenty minutes or if you are starting to feel anxious or worried, get up and do some relaxing activity until you feel sleepy. The anxiety of not being able to sleep can make it harder to fall asleep.28

(Note: My interest in the subject was kindled by Mathew Walker’s monograph “Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams”29 from which I have heavily borrowed for this essay. I found the experiments about the impact of sleep on learning new facts especially impressive. I have been repeatedly telling my students about it, with apparently little impact on their reading habits)

References

| ↑1 | https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/tom_hodgkinson_527586 |

| ↑2 | Walker M. Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams. Publisher Penguin, UK. 368 pages |

| ↑3 | Cirelli, C., and Tononi, G. (2008). Is sleep essential? PLoS Biology. 6, e216. |

| ↑4 | https://www.sleepadvisor.org/can-you-survive-without-sleep/ |

| ↑5 | L. A. Erland and P. K. Saxena, “Melatonin natural health products and supplements: presence of serotonin and significant variability of melatonin content,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2017;13(2):275–81. |

| ↑6 | A. Yang, A. A. Palmer, and H. de Wit, “Genetics of caffeine consumption and responses to caffeine,” Psychopharmacology 311, no. 3 (2010): 245–57, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4242593/. |

| ↑7 | Sakai J. How sleep shapes what we remember—and forget. PNAS 2023; 120 (2) e2220275120; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220275120 |

| ↑8 | G. Martin-Ordas and J. Call, “Memory processing in great apes: the effect of time and sleep,” Biology Letters 7, no. 6 (2011): 829–32. |

| ↑9 | S. Cohen, R. Conduit, S. W. Lockley, S. M. Rajaratnam, and K. M. Cornish, “The relationship between sleep and behavior in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a review,” Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders 6, no. 1 (2011): 44. |

| ↑10 | A. W. Buckley, A. J. Rodriguez, A. Jennison, et al. “Rapid eye movement sleep percentage in children with autism compared with children with developmental delay and typical development,” Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 164, no. 11 (2010): 1032–37. |

| ↑11 | S. Sarkar, M. Z. Katshu, S. H. Niza mie, and S. K. Praharaj, “Slow wave sleep deficits as a trait marker in patients with schizophrenia,” Schizophrenia Research 124, no. 1 (2010): 127–33. |

| ↑12 | D. J. Foley, A. A. Monjan, S. L. Brown, E. M. Simonsick et al., “Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities,” Sleep 18, no. 6 (1995): 425–32. |

| ↑13 | M. F. Bergeron, M. Mountjoy, N. Armstrong, M. Chia, et al., “International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development,” British Journal of Sports Medicine 49, no. 13 (2015): 843–51. |

| ↑14 | Ken Berger, “In multibillion-dollar business of NBA, sleep is the biggest debt” (June 7, 2016). Quoted by Walker, Matthew. Why We Sleep (p. iv). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.chapter 6, footnote 12. |

| ↑15 | N. D. Volkow, D. Tomasi, G. J. Wang, F. Telang, et al., “Hyperstimulation of striatal D2 receptors with sleep deprivation: Implications for cognitive impairment,” NeuroImage 45, no. 4 (2009): 1232–40. |

| ↑16 | A. S. Lim et al., “Sleep Fragmentation and the Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline in Older Persons,” Sleep 36 (2013): 1027–32; |

| ↑17 | O. Tochikubo, A. Ikeda, E. Miyajima, and M. Ishii, “Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure monitored by a new multibiomedical recorder,” Hypertension 27, no. 6 (1996): 1318–24; |

| ↑18 | Foundation for Traffic Safety. “Acute Sleep Deprivation and Crash Risk,” accessed at https://www.aaafoundation.org/acute-sleep-deprivation-and-crash-risk. |

| ↑19 | Van Cauter E, Knutson KL. Sleep and the epidemic of obesity in children and adults. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008 Dec;159 Suppl 1(S1):S59-66. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0298. Epub 2008 Aug 21. PMID: 18719052; PMCID: PMC2755992. |

| ↑20 | Virginie Bayon, Damien Leger, Danielle Gomez-Merino, Marie-Françoise Vecchierini & Mounir Chennaoui (2014) Sleep debt and obesity, Annals of Medicine, 46:5, 264-272, DOI: 10.3109/07853890.2014.931103 |

| ↑21 | Reutrakul S, Van Cauter E. Sleep influences on obesity, insulin resistance, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2018 Jul;84:56-66. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.02.010. Epub 2018 Mar 3. PMID: 29510179. |

| ↑22 | Walker, Matthew. Why We Sleep (p. 181). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. |

| ↑23 | Irwin MR. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015 Jan 3;66:143-72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205. Epub 2014 Jul 21. PMID: 25061767; PMCID: PMC4961463. |

| ↑24 | Hakim F, Wang Y, Zhang SX, Zheng J, Yolcu ES, Carreras A, Khalyfa A, Shirwan H, Almendros I, Gozal D. Fragmented sleep accelerates tumor growth and progression through recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages and TLR4 signaling. Cancer Res. 2014 Mar 1;74(5):1329-37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3014. Epub 2014 Jan 21. PMID: 24448240; PMCID: PMC4247537. |

| ↑25 | E. L. Arbon, M. Knurowska, and D. J. Dijk, “Randomised clinical trial of the effects of prolonged release melatonin, temazepam and zolpidem on slow-wave activity during sleep in healthy people,” Journal of Psychopharmacology 29, no. 7 (2015): 764–76. |

| ↑26 | Dr. Daniel F. Kripke, “The Dark Side of Sleeping Pills: Mortality and Cancer Risks, Which Pills to Avoid & Better Alternatives,” March 2013, accessed at http://www.darksideofsleepingpills.com. |

| ↑27, ↑28 | NIH Medline Plus (Internet). Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine (US); summer 2012. Tips for Getting a Good Night’s Sleep. Available from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/magazine/issues/summer12/articles/summer12pg20.html. |

| ↑29 | Walker, Matthew. Why We Sleep (p. iv). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition. |

| ↑30 | Antza C, Kostopoulos G, Mostafa S, Nirantharakumar K, Tahrani A. The links between sleep duration, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol. 2021 Dec 13;252(2):125-141. doi: 10.1530/JOE-21-0155. PMID: 34779405; PMCID: PMC8679843. |

Be First to Comment