‘…every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future.’ —OSCAR WILDE

Jaguar and an Eye-catcher

A black shining Jaguar XF always arrests my gaze as long as it is in front of my eyes. But this time, my eyes shifted focus to the man who came out of it, just as a uniformed chauffer came around to the door and opened it gently. The man looked nothing less than a movie star. Medium height, white hair combed back tidily, neatly groomed grey beard, aviator shades, dark blue striped suit, sparkling white shirt and in place of a necktie, a bolo tie of silver with a large amethyst at the centre.

From the other side of the Jaguar, stepped out a stunning young girl in a black suit and started walking with him towards the hospital.

I was walking out of the same hospital with RD at that time. He found me staring at the stylish man and asked, ‘Do you know him?’

‘No, I don’t. Who is he?’

CME in 2015

RD replied nonchalantly, ‘He is Manjunath; he works with our hospital.’ I had come to attend a CME (continuing medical education) organized by this famous multispecialty hospital in the Delhi-National Capital Region. RD is an old friend, an interventional radiologist, who works at the hospital and lives close to my house.

I was planning to return home with him, when this stylish man attracted our attention.

‘What specialty is he? A cardiologist?’ My question betrayed my belief that cardiologists are supposed to be the richest people.

RD turned sharply towards me, surprised by my question. A moment later, he smiled and said, ‘He is not a doctor, but he is richer and more influential than most doctors!’

I must have overlooked something. ‘What does he do?’

RD’s smile broadened, ‘You should ask what he doesn’t do! He is an entrepreneur! His is an interesting rags to riches story.’

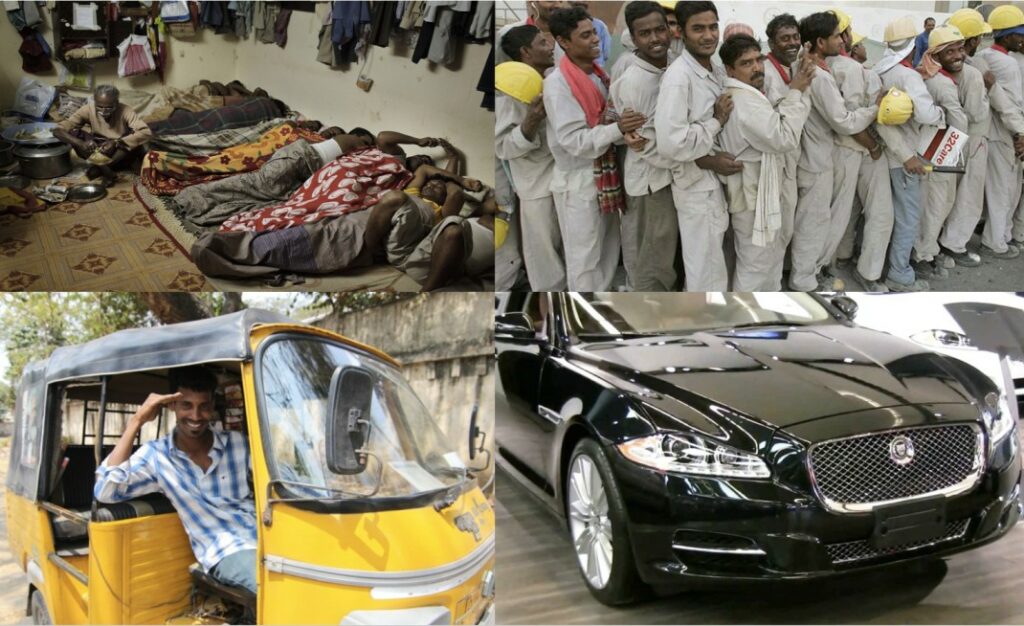

Rags to Riches Story

I looked at RD enquiringly. RD started, ‘Normally he is so busy, that you cannot get him to talk about himself. On our last annual day, we had a celebration of sorts, in which I happened to get a seat at his table and he was in a talkative mood.’

‘So what is his story?’ I was interested.

Right then RD’s driver brought his car to the portico. We settled in the car; RD gave some directions to his driver, and then started answering my question. ‘Manjunath is a self-made man who has created a specialized field for himself and is 7% owner of this hospital where I work.’

RD appeared very impressed by this man, ‘Let me start from the beginning. He lost his father when he was around 20, still studying in Class XI. There was a prolonged illness before the death, and the family was left bankrupt. Besides, Manjunath’s father, who was a vegetable vendor, had taken loans to run his business. So, the boy dropped out of school after his father’s demise and started looking for a job.

Searching for a Job!

‘He tried many things in India, but nothing worked out. After working for 3 years in various capacities, Manjunath went to one of the Gulf countries as a labourer, and worked there for the next decade-and-a-half. He worked as an unskilled labourer at construction sites, as a waiter in restaurants and God knows what else. Later, he ran a street-side kiosk selling groceries. By the turn of the century, he got fed up, picked up his savings and came back to Delhi. He then bought a second-hand autorickshaw and became an autowallah.’

I was finding it difficult to reconcile the image of the impressive man with a ‘tuk-tuk’ (three-wheeler) driver. I asked, ‘How did he manage to become so rich?’

RD said, ‘It was around this time that he got married and he attributes the change in his luck to his mother-in-law.’

‘Did he marry into a very rich family?’

Autowalla’s Mother-in-law

‘Not at all. He married an old acquaintance from a lower middle-class family. The father of the girl was in government service. One day, he took his mother-in-law to a private hospital that was empanelled by the Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS). The doctors advised that she be kept under observation in the hospital for some time. He left his wife and her mother in the hospital and went back to sleep in his auto parked outside the hospital.’

I was getting a bit impatient by now. ‘You were going to tell me how he became rich,’ I protested.

RD laughed. ‘That is exactly what I am telling you. This incident was the turning point. Manjunath woke up to the sound of someone asking the same question over and over again—Where can I get a taxi? And no one seemed to be replying.

Manjunath soon realized that the question was being asked in Arabic, so no one could understand it.’

Good Samaritan

RD continued, ‘Manjunath was very familiar with Arabic, so he rushed to help that man, who had come to India for a hip replacement surgery. Manjunath looked after him for the next few days. He helped the man get all the investigations done, and found a reasonable place for his relatives to stay in. The Arab then requested Manjunath to act as an interpreter during his interactions with doctors. Manjunath did so as a Good Samaritan.’

‘Did the Sheikh give him a bag of gold before going back?’ I asked in jest.

‘Sort of! But not in the way you mean. The Sheikh did pay him handsomely, but more important, he gave Manjunath an idea for a new profession! Manjunath soon became an interpreter/facilitator.’

‘How can an interpreter earn so much?’ I asked dubiously.

RD ignored my question. ‘Within a few years, Manjunath became a popular interpreter. He remained in touch with all the people he helped. Soon, a proportion of the patients from the Gulf countries sought him out for help and advice. He would advise them on where to stay, where to shop, which…’

‘But you still have not answered my basic question—how much can an interpreter earn?’

An Interpreter

‘One day after a few drinks he said few things which you normally do not hear. He said he started charging at both ends!’

‘What both ends?’ I did not understand.

‘Both ends means, if he took a patient’s family to a hotel, he charged the patient for his service and the hotel for bringing in a client. In fact he started getting a large commission from hotels seeking business, especially during the lean season.’

‘Yes, I am aware that all taxi drivers get such commissions from hotels.’ I was beginning to see the light.

RD gave his driver some directions and then addressed me again, ‘It may have started with hotels and shops, but it soon progressed to investigations at laboratories and advanced imaging centres.’

I had heard about the doctor–laboratory nexus or the doctor–imaging centre nexus, but this was a new angle for me. Coming from a radiologist, it sounded plausible though.

The Nexus

RD then added the most explosive sentence without warning, ‘It also extended to clinicians, who wanted to earn more.’

‘What?’ I could not believe it.

RD coolly said, ‘In Manjunath’s own words, doctors are willing to give more than 25% of their consultation fees as well as procedure/operation fees to get more patients!’

I thought RD was now treading on thin ice. Very thin ice. I asked him, ‘Isn’t that unethical and improper?’

RD quoted the entrepreneur again, ‘When I raised this point that night, Manjunath had replied, “I am primarily a businessman! I sell my wares to the highest bidder. It is for doctors to think about ethics. If they don’t, why should I?” And I agree with Manjunath.’

I did not know what to say.

Expansion of Business

But RD went on, ‘Manjunath has a staff of about 90 people today. Of these, 60 are interpreters of different languages. He donates handsomely to political parties. When my hospital was being made and the owners were looking for people who could invest in the venture, Manjunath was one of the major contributors. He is now a member of the board of trustees and has a contract to supply interpreters for all foreign patients. He also runs a coordination agency to arrange tourist visits for patients to Agra, Goa or Khajuraho, while they are waiting for a drug to take effect.

He, in fact, controls the interpreter business in many big hospitals today. His office has a network in about 20 countries to guide patients in India. It is also in close touch with various offices to arrange for extensions of patients’ visas, if required.’

I asked RD, ‘You are a radiologist; many of your close friends must be running diagnostic centres. Are such things common?’

His answer was very frank, ‘It was news to me when I heard it for the first time from Manjunath. Later, I talked to my friends and became aware that most diagnostic centres and laboratories fix the price of various tests, keeping in mind their overheads, including the efforts and expenses of their marketing departments. If a doctor can promise a certain volume of business to them, he or she can negotiate for discounts up to 30%–40% on the quoted price.

Discounts?

I do not know if such discounts are routinely being offered as incentives to people like Manjunath.’

The driver stopped the car in front of my house. I thanked RD for the ride and for opening my eyes to a new dimension of medical tourism.

Medical tourism is not a new phenomenon. In ancient Greece, pilgrims and patients came from all over the Mediterranean to the sanctuary of the healing God, Asclepius, at Epidaurus. In the eighteenth century, wealthy Europeans travelled to spas on the banks of the Nile. Today, we are in an era in which hospitals are more like spas and spas more like hospitals.1

Medical Tourism

India has become a popular medical tourism destination in the past decade or so because there are long waiting lists in the developed countries, and the cost of medical treatment is much lower in India, where complicated surgical procedures are conducted at one-tenth the cost in developed countries. Add to this the affordable international air fares, favourable exchange rates, easy communication via the Internet, and the state-of-the-art technology used in big Indian hospitals and diagnostic centres.2

It has been estimated that medical tourism could contribute Rupees 5000–10 000 crore (Rs. 50 000–100 000 million) to the revenue of up-market tertiary hospitals and account for 3%–5% of the total healthcare delivery market.

However, when tourists come through sources such as Manjunath, the quality of care that they get may be questionable. Many of them may be guided to dubious providers who offer better incentives to the middleman. This may lead to big promises and disappointing results. What will this do to our country’s image as a service provider?

I am a Businessman!

Another question was troubling me. I remembered a statement attributed to Manjunath. ‘I am primarily a businessman. I sell my wares to the highest bidder. It is for doctors to think about ethics. If they don’t, why should I?’ Were doctors really bidding? Were they willing to pay a part of their earning as an incentive to people like Manjunath, to get more patients? It was surely unethical and doctors could be punished if caught. Was Manjunath right in assuming that he had no liability? In a transaction between two people, when one can be punished, how can the other remain untouched?

I narrated this story and expressed my doubts to a friend of mine (Dr NN) who is the Convener of the Medicos Legal Action Group and ex-president of the Indian Medical Association (Chandigarh). He said that legal action is possible only if the patient complains. A third party or an activist cannot do anything about it. Then he went on to raise his own set of questions.

A Few Questions

1. Would it be more ethical to charge a patient Rs. 6000 for a consultation/procedure/investigation without giving a cut or commission than to charge him `4000 for the same consultation/procedure/investigation but giving `500 as a cut/commission to a middle person?

2. Doctors/hospitals are equated with traders and other service providers under the Consumer Protection Act. A doctor’s clinic is considered a centre of commercial activity when the government charges for utilities such as water and electricity. If we agree that a doctor’s or a hospital’s services are commercial activities subject to the same laws as any other business activity, why should there be different standards for this ‘commercial activity’? We accept that the wholesale rate of soap is different from the retail rate despite the fact that the maximum retail price is the same. We accept that an insurance agent may be paid a 30% commission to get a client as a just reward for his hard work. We also agree that an employee of a pharmaceutical company may be sent on a trip abroad for meeting his targets, as a bonus and is a justified reward and ethical business practice. Why then should we not apply the same rules of business to medicine, which is a ‘commercial activity’?

More Questions

3. There are many agencies that benefit from a doctor–patient relationship and are indirectly paid by patients, though they do nothing directly to ameliorate the suffering of the patients. There are legal luminaries who are happy to have yet another avenue of earning and whose fees are ultimately (even if initially paid by the doctor/hospital) paid by the patients. The fees charged by the facilitators of the National Accreditation Board of Hospitals (NABH) and other accreditation agencies are also paid by the patients ultimately. There are insurers, whose enormous infrastructure, staff and profits are sustained by the patients. On the face of it, they help patients, but in the final analysis, they earn profits from them. Then there are the touts (like Manjunath) who may come to own 7% of a hospital by facilitating patient investigations and treatment through contacts. (I could add that the entire administrative staff of a hospital, including departments of human resources, finance, transport, legal issues, landscaping, security, conveniences and marketing fall under this category.) The simple doctor–patient relationship has now become complicated beyond recognition.

4. Medical equipment suppliers, pharmaceutical companies and laboratory equipment manufacturers all have a responsibility towards their shareholders to make the maximum profit. A doctor who solicits clients/business for himself, however, is considered a flesh-eating devil. I have never heard of a chemist having to give streptokinase to an acutely ill patient without payment. It is only the doctor who is required to use all the resources at his command to treat, irrespective of the fact that he may not receive any payment.

GPs as Touts!

5. In India, it is usually the general practitioner who acts as a tout. Unfortunately, we focus on the high-end specializations, forgetting that it is the quack, the semi-qualified general practitioner and the other so-called ‘doctors’ who earn more from the procedure that a superspecialist carries out than does the superspecialist himself.

Maybe my friend wished to suggest that in the era of corporate medicine, medical ethics as it existed is an anachronism. Surprisingly, such a need to revise the ethical guidelines has not been felt in the western world, where corporate medicine is the norm.

Do these questions reflect the eternal conflict in developing countries between values and an affluent lifestyle? Does it have anything to do with the dreams of an affluent lifestyle which are beamed into our homes through television, and which tend to disconnect us from the reality of our masses?

Sin for a Doctor to be Affluent?

Is ‘earning money and acquiring an affluent lifestyle’ not compatible with the ethics of a doctor’s profession? I do have differences with Dr NN on several counts, but his questions need to be answered.

Unfortunately, I do not have clear answers to the questions raised by him and the likes of Manjunath. So, I have decided to put these points across to erudite readers because I believe that some of them will definitely find answers to these questions.

(Note:

The names and places are fictitious, but the issues are real. Any resemblance to a person living or dead is purely coincidental. I am grateful to Dr Neeraj Nagpal, Convener, Medicos Legal Action Group, ex-President, Indian Medical Association, Chandigarh for his inputs.)

This paper was originally written in 2015 and published in National Medical Journal of India.3 Only changes I have made in the blog are that subheadings & cartoons have been added to make reading easier. The text has been reproduced with permission from the Editor of National Medical Journal of India and the Author is grateful to him for permissions.)

References

| ↑1 | Chakravarthy KK, Ravi Kumar CH, Deepthi K. SWOT analysis on medical tourism. In: Conference on tourism in India—Challenges ahead. Indian Institute of Management,15–17 May 2008. Available at http://dspace.iimk.ac.in/bitstream/2259/577/1/357-364+Kalyan.pdf (accessed on 7 Dec 2014). |

| ↑2 | Dawn SK, Pal S. Medical tourism in India: Issues, opportunities and designing strategies for growth and development. Int J Multidisciplinary Re 2011;1:185–202. Available at http://zenithresearch.org.in/images/stories/pdf/2011/July/16%20SUMAN%20KUMAR%20DAWN.pdf (accessed on 7 Dec 2014). |

| ↑3 | Anand AC. Manjunath. (Speaking for myself). Natl Med J India 2015; 28(2): 93-95. |

A nice peice sir. Relevant questions. But I do not think that our society will be able to answer these questions well as we have grown up with the doctor-bhagwaan-ka-roop ideology and ‘bhagwaan’ can’t be seen profiteering from any endeavor.

Till we break these shackles, we may not be able to project a ‘more human’ and ‘less divine’ image.

And when we do break these shackles, we end up losing the nobility of the profession.

Therein lies our biggest power and ironically our biggest curse.

Brilliant piece sir